Books

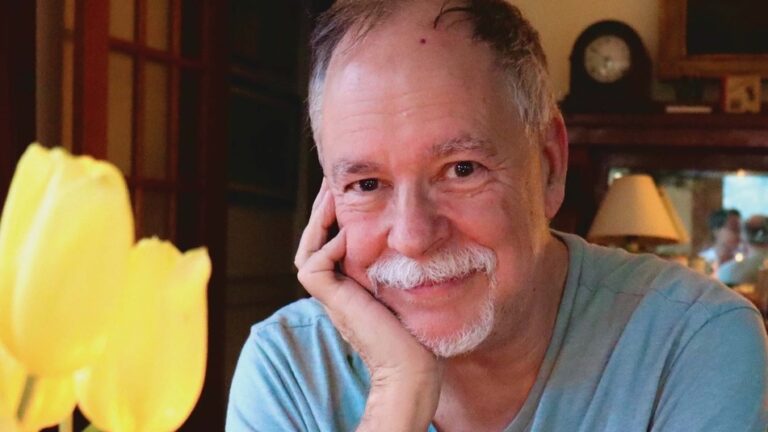

Maguire — author of the original novel — discusses all things “Wicked,” including his new book in the series hitting shelves soon.

Pay no attention to the man behind the curtain.

Actually, let’s give him some spotlight.

If you went to elementary school in New England in the late ‘80s and early ‘90s, there’s a chance Gregory Maguire taught you creative writing while he was writing “Wicked.”

“I worked around New England in dozens and dozens of schools as a self-employed journeyman/jack-of-all-trades/author-in-residence/ writing instructor, brought in for a few days. That’s really how I made my living up until the time ‘Wicked’ got published,” the Concord resident tells me in a recent phone interview.

While the Tufts and Simmons alum “was writing ‘Wicked’ and living in London, I’d come home for 10 weeks every spring and make half my annual income working in New England schools, then go back to England and keep writing.”

The journeyman never could’ve dreamed of the journey his own creative writing would take him on.

Unless you’ve been living under a rock under another rock, you know “Wicked,” his 1995 origin story about the Wicked Witch of the West.

Despite the lime green blanketing the world right now for Gregory Maguire’s story, the Concord resident assures me:

“I’m just a Boston schlub. You wouldn’t notice me if I was walking down the street dropping my Dunkin’ donuts, spilling my coffee on some old lady waiting to cross the street to Central Square, and me neglecting to say sorry,” he deadpans. “I’m just a normal Boston jerk.”

In our conversation, the former Simmons professor is warm, quick-witted, laughs easily, paints a vivid picture with his words — even though I’m interrupting his afternoon nap. (Solid teacher material.)

The Albany, New York, native arrived in Boston in 1977 for grad school, earning his master’s in children’s literature from Simmons College in 1978, and doctorate in English and American literature from Tufts University in 1990.

Today, with dozens of books both for adults and kids under his belt — including the “Wicked” series — Maguire, 70, lives with his husband, the painter Andy Newman, in Concord. Their three kids are in their 20s. (“They’ve known about ‘Wicked’ since before they knew which end of the spoon to use.”)

I called to talk about his own origin story, thoughts on the blockbuster movie and Tony- and Grammy-winning Broadway musical, the promo budget, his next tale about the Wicked Witch of the West hitting shelves soon — and how “The Wizard of Oz” is like the Gettysburg Address.

You wrote “Wicked” in London, but had some notes about the idea when you lived in Jamaica Plain.

I must’ve been thinking about it in Jamaica Plain, because I do have one or two pages of handwriting — but I didn’t start it until I left [for] London.

What sparked the story?

Unlike a child, a story has more than one moment of conception.

[laughs]

One moment was, as a kid, watching the 1939 film. My parents were strict about TV, but relented for “The Wizard of Oz.” They thought it was a nice, fun film that couldn’t hurt anybody. Of course, we all had to go into 10 years of therapy to get over Flying Monkey Syndrome. [laughs]

Yup. Terrifying.

Everybody in the neighborhood watched it. I was the boss kid, so I organized everybody into an improv troupe in my backyard. I’d assign parts. We’d do it, then I’d say, “People, listen up! We’re going to shake it up a little bit. Captain Hook is in the show this time. He’s going to marry the Wicked Witch and they’ll have kids.” The younger kids scowled and pouted: “That’s not fair! [Hook] doesn’t belong in this.” I’d say, “He does. I’m the author.”

I love this. This is your origin story.

I discovered then: If you take something everybody knows, and change just one thing, the story can’t conclude the same way.

The second moment: In London, I became interested in a murder [case] England was obsessed with at the time. I needed to get my mind around the question: What is evil?

I decided to marry that with my love of “The Wizard of Oz,” and my interest in fairy tales and children’s stories, the ways in which they instruct us about moral behavior for the rest of our lives.

And also with my own increasing unhappiness with the actual story — the Wizard is guilty of terrible exploitation of innocent Dorothy, sending her off into grave danger to do a job he’s too frightened to do himself. He never gets any comeuppance for it.

That’s true.

All those things rolled together, and “Wicked” became the story of a green-skinned woman — who is not the saint Broadway and Hollywood make of her.

She’s a complicated human who does some grave damage, but has hopes for improving the world.

I haven’t seen the adaptations, but I’m assuming they’re very different from the book. The book feels closer to R-rated. There’s some risqué stuff. The movie is only rated PG.

And there’s a reason, Lauren, I intentionally put R-rated material in the opening of the novel. It’s not very R-rated — puppets having sex, but kind of kinky sex. I did that on purpose so that anybody picking up the book deciding whether it was suitable bedtime reading for their 10-year-old would be able to tell right away. “No.”

[laughs] What do you think of the adaptations ?

I love them. [When I first saw the play] I had to come around to accepting a couple of twists that they’ve made — cutting out characters and a couple of decades.

Even though the characterizations of Elphaba and Glinda and the rest have become more stereotyped, almost parodies, the moral lessons and the emotions you leave with are not much different than the feelings I hope you have when you finish my 400-plus-page book.

In all instances you need to go to the bathroom — but that’s not the feeling I’m talking about.

[laughs] Where did you first see the movie?

In New York City. There was a private preview, for people in the “Wicked” theater community from the past 21 years. Then I took my family to LA for the Hollywood premiere so they could meet the stars.

Even though I’d seen the sets, I still found [the finished film] impressively grand and beautiful. It just smacks you in the face.

What feeling did you get, watching it for the first time?

I was catatonic. I felt the way people feel when they’ve been in a car accident and everybody’s shouting through the broken glass: “Don’t move.” And you’re thinking to yourself, “I don’t know if I can move, but I’m certainly not going to try until there are medical professionals here.”

[laughs] I can see that.

I’ve been waiting for this, in some ways, for 27 years. I think I signed a contract with Universal Studios 28 years ago. I just gaped. The second time I saw it, I found it very moving and beautiful.

If I had any criticism, I was afraid the high-gloss, Willy Wonka candy-color sets would make it so juvenile you’d lose touch with the fact this is a moral fable.

But I decided that the bright, distracting colors and activity of the Emerald City was a bit like the Circus Maximus in Rome: giving entertainment and bread to the citizens to distract them from the fact that they’re paupers, and from the reality that their leader has no pants, effectively.

Do you find this story a timely message now?

Well, it’s not up to me to deconstruct the American political moment in 2024. [laughs] I wrote this novel nearly 30 years ago, and at the time, I thought it was possibly too retro. That’s an interview question you have to take up with the world, not me. [laughs] That’s their fault. That’s on them.

The marketing budget on the movie is mind-boggling. Being the author and seeing all this for your work — I can’t imagine.

Oh, it’s — just think of all that green ink. I hope it’s water-soluble. I have not heard, and doubt I will, how much money is spent on the promotion, but I’ve heard it murmured by people who work in Hollywood that it can’t be any less than eight figures. Possibly nine. I don’t know.

You must feel like your story has just taken over the world.

Did you ever see the original “Ghostbusters”?

Yes.

You know when the ghosts are over Manhattan, and the entire sky is luminescent with ghostly ectoplasm? I feel like a kind of emerald green shadow is cast upon my life, as far as I can see to the left and right.

[laughs] I bet.

I’m lucky this kind of success happened in the second half of my life when I’ve learned to keep my feet on the ground.

You’ve got a new book in the series: “Elphie” releasing in March, which centers on Elphaba’s childhood. Her “missing years,” you told me.

Yes, its bones come from two or three scenes cut from the original “Wicked” manuscript, [which was] near 580 pages. It was recommended I drop scenes from when Elphaba was about 10 or 12.

I actually think how a child is at that age is really important. We’re becoming our adult selves, but we have almost no control. That’s a ravishingly interesting time in someone’s life. When I’m reading a biography, I don’t care what a person’s grandparents did — I want to know what they were like when they were 10. How they began to come into themselves.

Very true. And going back to your early days — you spent your earliest time in an orphanage.

Yes. An “infant home,” where kids were parked when their families couldn’t take care of them adequately. Kids were also adopted from there. My father, who lost his wife, and had three other kids at the time— my first mother died in childbirth when I was born — left me there until he got remarried. Then he and his second wife — my second mother — collected me. I was there about two years.

It’s interesting because, for someone who studies and works in fairy tales and children’s tales — that sounds like something from a fairy tale.

Oh, it does. I find I’m drawn to tales of children who are abandoned or lost or orphaned. I was drawn to them as a kid without knowing why, and I’m drawn to them as an adult. Fables about the orphaned beautiful daughter whose mother dies — those are deeply moving to me.

Stories of children making their way are universal, we all see ourselves in them. If anybody questions: “Why do you retell children’s fairy tales for grown-ups? What kind of an idiot are you?” I don’t have any apologies about having used whatever brain God gave me to write stories that I hope offer both challenge and consolation.

I’ve come around to realizing that if the arts are for anything, they’re to take us out of ourselves and put us back together so that we can be better equipped. That’s not much different than being a doctor, or working in public policy. It’s an attempt to help people on a case-by-case, reader-by-reader basis, to stay strong. That’s what I use reading for: to stay strong in my own soul. And that’s why I write as well.

Wow, that’s beautiful. I feel all of that. And Frank L. Baum’s original novel released in 1900 — almost 125 years ago — what do you think it is about “The Wizard of Oz” that’s so ever-appealing?

It’s a quintessential American tale. Dorothy has to survive, but even though she’s cast into a land of magic, magic does not enter into how she deals with her troubles. She’s full of grit. She’s dogged, like most pioneers. It’s a very American fable.

I consider “The Wizard of Oz” — along with “City Upon a Hill,” the Gettysburg Address, and Henry David Thoreau’s “Walden” — one of the founding texts of American character.

It teaches us who we are as a people — a people of self-determination, of pulling ourselves up by the bootstraps. A lot of that may be public relations, but it’s part of our national myth: the national myth of self-improvement and just getting on with it. And a lot of that isn’t myth.

That’s fascinating. I never saw the story in that light. Anything you want to add?

Just that if you’re gonna see the movie, use the bathroom before.

[laughs] Nice.

It’s the longest movie and yet you can’t unglue your eyes. You come out feeling a change — and I don’t mean that you have to go have your bladder detoxified.

Lauren Daley is a freelance writer. She can be reached at [email protected]. She tweets @laurendaley1, and Instagrams at @laurendaley1. Read more stories on Facebook here.

Boston.com Today

Sign up to receive the latest headlines in your inbox each morning.

Leave a Comment