Arts

“The Song is Still Being Written” about the Cambridge folk scene and Club Passim opens Sept. 12 in Boston.

Folk music, Barry Schneier wants you to know, is not dead.

“It’s well alive. Certainly in the Boston and Cambridge area,” Schneier tells me in a recent phone interview from his Plymouth home.

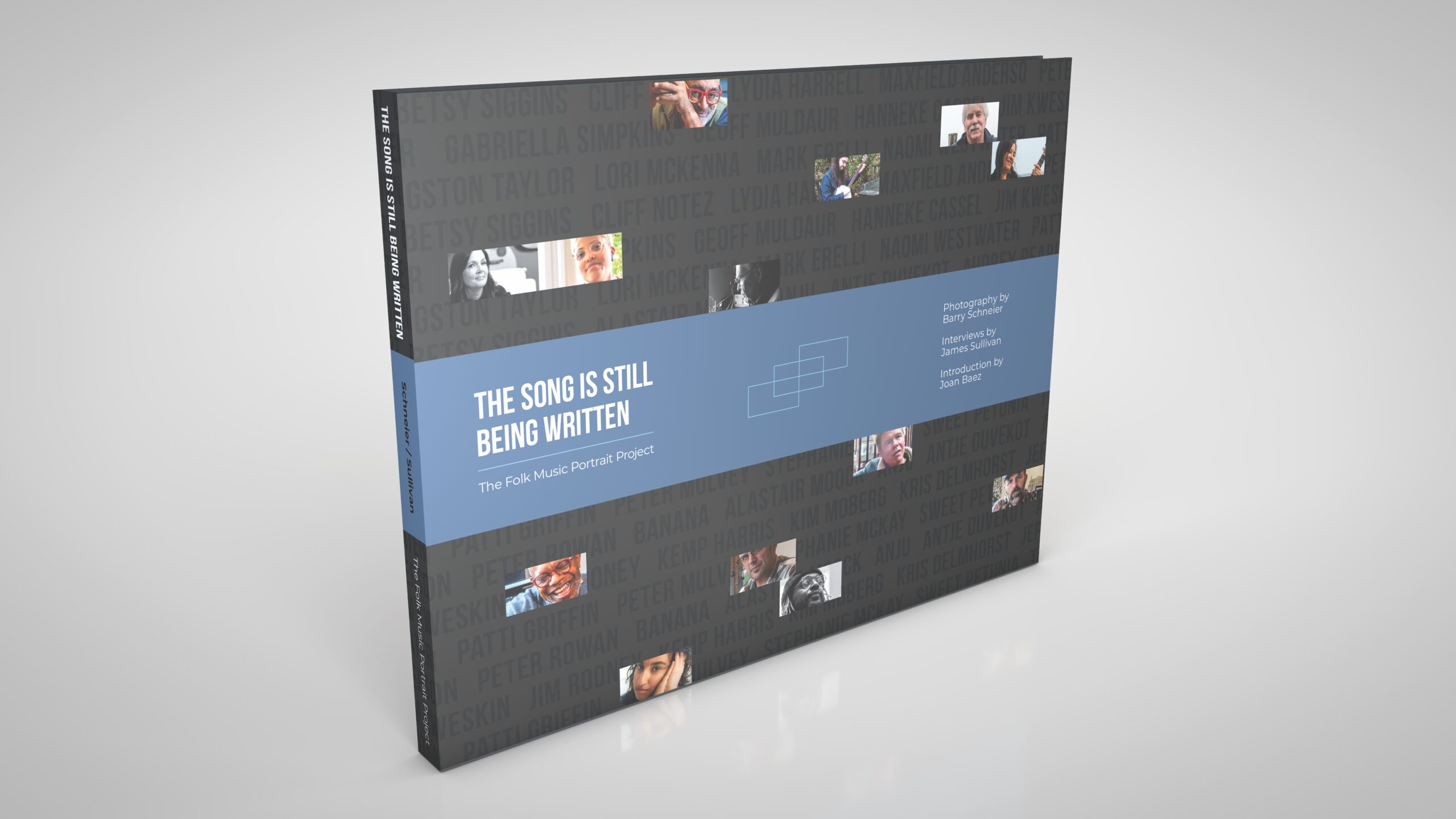

The title of his new photography book — and accompanying exhibit at Boston’s Folk Americana Roots Hall of Fame opening Sept. 12 — says it all: “The Song is Still Being Written: The Folk Music Portrait Project.”

That song is not just by older white guys, Schneier, 74, points out: “A lot of people have this impression that folk music is old white guys with guitars. It’s not,” he said. “All music is folk music.”

This idea is so beautifully simple, it’s a wonder no one hasn’t thought of it before. Because yes, folk is alive. Yes, folk has long loomed large in Boston and Cambridge. And yes, folk music is universal human music.

Here we see some three dozen artists, many with New England roots, from Gen Z to boomers, with varying beads on a single unifying thread: Club Passim. The necklace is the brainchild and passion project of freelance photographer Schneier.

His self-published book of portraits features stories from artists in their own words — told through interviews with freelance writer James Sullivan — about how they’re connected to Passim, nee Club 47, what they love about it. There’s also a foreword from Passim’s executive director Jim Wooster and managing director Matt Smith.

Artists range from the old guard — Arlo Guthrie, Jim Kweskin, Tom Rush, Joan Baez — to “that middle generation” as Schneier puts it — Lori McKenna, Vance Gilbert, Josh Ritter, Patty Griffin, Anais Mitchell — to what his website bills as the “fresh faces from the Folk Collective Initiative at Passim, including Naomi Westwater, Cliff Notez, and Kim Moberg, who are bringing new meaning to the definition of ‘folk music,’” according to the project’s billing.

Sure, the book is about Passim. But at its heart pulses something larger. I asked the 1972 Emerson College alum what he wants people to get out of his book:

“That folk music is not this music of older white people playing guitars. Folk music is music by the people, for the people. The music of the folks. It’s one of the true art forms that really is a personal self-expression,” he told me.

“It’s really a diversified community of singer/songwriters doing the same things that their predecessors did. Jim [Rooney] said: A lot of artists today are doing the same thing people like Tom Rush did years ago — traveling, sleeping on friend’s couches. Very few people are getting rich with folk music. They aren’t doing it for [money]. They’re doing it because they love the medium and community.”

Schneier self-published this book for love, not money: “This was a passion project. Hopefully we’ll sell enough books to at least get our costs covered,” he tells me with a laugh.

This will be Schneier’s second exhibition at FARHOF: he’s also currently part of “Bruce Springsteen: Portraits of an American Music Icon.“

I caught up with the Newton native ahead of his new exhibit to talk Boston, folk, photos, that famous Springsteen shot, and more.

Boston.com: So I love this concept. How did this book come about?

Barry Schneier: I pitched Passim in 2020. I said, You know, the roots of this genre lie heavily in your club. A lot of these artists are still performing today — people like Tom Rush and Chris Smither. Then there’s this middle generation — Lori McKenna, Mark Erelli, Josh Ritter. Then there’s a whole new generation of artists redefining what folk music is, singing about the issues they deal with — climate change, politics, gender identity, LBGTQ issues, racial issues. I said: Let’s tell these stories and link them together.

I like that you didn’t just take concert photos, but creative portraits that show artists at home or in interesting places — the ocean, the woods, a playground.

I’ve always loved portrait work. I wanted to go where they like to spend time, be creative, feel comfortable. I said, let’s photograph them in their environment as opposed to performance.

Tell me about this exhibit that opens Sept. 12.

It’s two rooms. One has enlarged photos from the book, text panels with information. The other room has artifacts from Passim, a recreated stage, large graphics on the walls, and black-and-white session shots.

That’s awesome. Tell me a bit about you. You grew up in Newton. Did you always want to be a photographer?

It was at Emerson where I really began photography. I started off a filmmaking major, but started a photography minor because I was interested in being, call it, a recorder of images.

I like that.

After graduation, I got hired by the Fine Arts department, assisting professors. In the meantime, I was a DJ, a roadie, always found myself embedded in music. I knew a lot of people in local bands. I was friends with some local promoters, one of their [clients] was Bonnie Raitt. That’s actually how the opportunity with Springsteen came about.

Right, one of your most famous shots is of young Springsteen at the piano in Cambridge in 1974.

I’d seen Bruce playing a bar in Cambridge. I was so blown away, I called my friends, the promoters. I said, “You gotta get this guy.” They got him to open for Bonnie at the Harvard Square Theater in May. That’s the show I photographed. Jon Landau was in the audience [reviewing the show for Boston’s Real Paper] and wrote: “I saw rock and roll’s future and its name is Bruce Springsteen.” So I was fortunate to be part of whatever it took to get him on stage in Boston that night.

“Bruce Springsteen: Rock and Roll Future” is the name of your Springsteen photo book, too. You told me you moved to LA for a bit, worked in video production, marketing, then moved back to Massachusetts. How did you get back into rock photography?

About 12 years ago, my kids came across my work and said, “Dad, you should really get this stuff out.” I created a website, and because I photographed Springsteen at an iconic performance, people took notice. I [eventually] published that book in 2019. Next thing I know, I’m back into the world of music.

How did you decide who to feature in this book?

We made a list. First it was: Who would we like to have? The it came down to: who we can get. [laughs]

[laughs] Right.

There’s a couple of artists we just kept missing, but I wanted the book done by September. We reached a point where we had to stop photographing. I’m very happy with the results. I wanted 30, and we got 37.

Who was on your original list?

Tom Rush, Jim Kweskin, Chris Smither, Lori McKenna. After a while, people in the folk music circle got wind of the project. Melissa Ferrick reached out. Someone mentioned Josh Ritter, so when he came through town, we got him to Passim for pictures. Same with Anais Mitchell.

I like the diversity. We have a range of backgrounds, ages and prominence. One-third of the artists are the Folk Collective, which is all the new voices in the Boston area.

What will strike you for a portrait?

Two things. First, I want to photograph somebody in the environment they feel comfortable in, that says something about who they are — it could be a place they write or create, a place they feel inspired by. I wanted to find places that reflected who they are. For instance, Alastair Moock wanted to shoot at the Cabot Theatre in Beverly — he performs there; he likes the place.

Audrey Pearl, we walked around [her neighborhood] by a playground. I said, “Why don’t you get on that swing?” She did. So part of it was having a little fun. I wanted the photos to be whimsical. I wanted people to look at the photos and get interested in who the artists are. I’m at the point now where I don’t mind asking people to do things — the worst that’s going to happen is they’ll say no.

I love the photo of Kim Moberg standing ankle-deep in seaweed in the ocean.

I love that one, too. We took some photographs at her home on the Cape. I said do you mind standing in the ocean with your guitar? And it just works.

It does. The shot of Chris Smither is great, too, with his dog under the table.

We got some nice shots of him playing, then we’re talking, sitting by the table, and his dog comes in, just lays underneath the table. I said: “That’s the shot.’

You self-published the book. People can get it on your website. Will it be in bookstores?

If people will put it there.

[laughs] OK.

[laughs] I haven’t gone to that point yet. When I did Springsteen book, I was lucky that I had a publisher to take care of all that. I have to be my own marketer here.

Right. So did you find any common threads?

The common thread is everybody was totally accommodating and excited about the project. I’ve been a fan of Tom Rush since my college days, so when I’m up in the studio and he starts playing, “Urge for Going,” I’m saying, “Is this really happening?”

I go to Lori McKenna’s house and she’s got this award here, a note from Tim McGraw there, this platinum album from her work with Lady Gaga — and she’s just the most humble person you could ever meet. She was thrilled I was taking her photo. It’s like, are you kidding me?

Especially the new artists, the Folk Collective, they all said to me, “This is so you’re creating this document, this exposition, that shares what we’re doing.” That was wonderful to hear. So that was [something] in common: the way everybody embraced the project. Another common thread was that they all aspired to play Passim at some point.

What portraits strike you as favorites?

I love the one of Gabriella Simpkins. She lives on the Cape, we met at a park she likes. We were walking through the trails in the woods, the light was just coming in a certain way, and I said, “OK, stand over there, hold your guitar this way, and just look up.” I love the one of Kemp Harris at home in Cambridge. And Melissa Ferrick.

With those cat socks. [laughs] I love that one.

[laughs] I showed her the photograph, she goes, “Oh, you got my kitty socks in there!” She was so excited about that.

So you mentioned the themes of diversity, and that folk is alive. But another point of the book is Boston’s role in the folk scene.

I’m glad you brought that up. I grew up going to Club 47, and knew it had a history — Joan Baez getting a start here — but the idea that so many artists, at some point, not only had played on Passim’s stage but wanted to play the stage. That club is the epicenter of the folk revolution. The exhibit is really about that, as well. The exhibit celebrates Boston as a music city. The philosophy of the Folk American Hall of Fame is that folk music has a past and present— but also as a future. And here we are celebrating all of that. And that’s why I think my project jives so well with them, because the philosophy is the same. The book celebrates the past, the present and into the future.

Portraits aside, in general, what will strike you for a photo?

That’s a great question. We live in a three-dimensional world, always in motion. I like a photo where you sense there was motion before or after the photo was taken. That you caught something in the middle of it happening. That you saw something in the middle of a lot of other things.

I love that.

Like at that Springsteen show — there’s another shot I took of him during that show, where he’s a little bit blurred. The whole band’s facing front and he’s facing back, and you feel the energy, the action. I like when you look at the photo and sense that there are other things outside the frame. That the road doesn’t end at the corner of the frame — the road continues on.

Interview has been condensed and edited.

Lauren Daley is a freelance writer. She can be reached at [email protected]. She tweets @laurendaley1, and Instagrams at @laurendaley1. Read more stories on Facebook here.

Need weekend plans?

The best things to do around the city, delivered to your inbox.

Leave a Comment